Principles

The consultation

When a person experiences an illness they look to health professionals to provide a solution. Ideally, a partnership between patient and doctor should be established that allows the best possible outcome for the patient.

The starting point of the whole process is the medical consultation. The purpose of the consultation is to assess the impact that the condition is having on the patient, establish the nature of the underlying cause of the problem, make a diagnosis, decide – between both the doctor and patient – on a suitable course of treatment and then monitor how effective this treatment is being.

You, as the patient, are the main source of information about your problem, and the information you give is crucial to help the doctor understand the nature and impact of the problem and to arrive at a diagnosis and a course of treatment.

It has been shown that musculoskeletal problems (problems that affect the joints, ligaments, tendons or muscles) are often not fully assessed by doctors and that as a result many of the problems are not managed as well as they might be. It is known that the earlier in the course of the disease that the problem is identified and treatment started the better the outcome for the patient. So a good consultation is really important.

Patient Partners have an important role in giving health professionals insight into how musculoskeletal problems affect individuals’ lives and how the professionals need to ask the right questions to gain the information they require to make a diagnosis.

Your role as a Patient Partner is helping health professionals understand how to assess musculoskeletal problems effectively and efficiently by using history and examination. You will learn about a screening history and examination that enables the doctor to identify if someone has any musculoskeletal problems and also learn the assessment by full history and examination of those problem joints identified. You will learn about the assessment of some of those joints that do or have affected you.

It is clear that if the doctor has had specific training in performing a complete assessment of a musculoskeletal problem, with the added advantage of working with a Patient Partner, this process will be more efficient and will produce benefits for both doctor and patient alike.

This is what makes the Patient Partner programme so valuable.

Matching expectations

A medical consultation is a two-way process. Information must flow in both directions between doctor and patient. This is best achieved if both parties understand each other’s expectations and if both know how to ask the right questions to get the information they need. The doctor will be interested in the disease but the patient is more concerned about the illness and problems that the disease produces. So let us just take a moment to consider: what is the purpose of the consultation from the patient’s point of view? And, what is the purpose of the consultation from the doctor’s point of view?

The consultation from the patient’s perspective

Musculoskeletal problems may arise quite quickly, or may develop gradually over time. When the patient sees the doctor for the first time with this particular problem the sort of questions that may be going through his or her mind is:

- What is wrong?

- What will happen to me?

- What can you (the doctor) do about it?

- What can I do about it?

- Will I get better?

- Will I get worse?

At later consultations, people will be asking questions such as:

- Am I getting better?

- Am I receiving the best treatment?

- Are there any other treatments available?

- Why am I not improving? Or: am I improving quickly enough?

- Will my symptoms get worse?

- Will I become permanently disabled and lose my job or independence?

It is the role of the doctor to answer these questions as best as he or she is able and to work with the patient to resolve the issues. Patients will be seeking information and also reassurance.

The consultation from the doctor’s perspective

The doctor will have many questions that need to be answered either by asking the patient or by carefully observing and examining the person.

There are many different types of conditions that the doctor will have to consider during the consultation. These are listed in Part 2 and will be discussed as we encounter them in the manual.

The questions a doctor will wish to be answered include:

- What is the problem?

- Is there an abnormality? And if there is,

- What is the nature of the abnormality?

- What is the effect of the abnormality?

- What is the cause of the abnormality?

- Are there any predisposing risk factors? (Predisposing risk factors are features that make a person more likely than the average to get a disease. For arthritis, these factors include obesity, lack of exercise, smoking, a family history of the condition or other illnesses such as psoriasis (a skin condition).

- Are there any complications? (e.g. some diseases can affect other parts of the body, or treatments may have side effects)

- What is the course of the disease?

- What is the response to treatment?

- What are the physical and psychosocial impacts of this condition on my patient.

Special note

The terms “abnormality” or “abnormal” are used medically to describe something that is outside what is seen in the majority of the population, such as swelling or loss of movement of a joint or a laboratory investigation result. These terms are not judgemental or pejorative in nature and are not suggesting that the patient is “abnormal”, but knowing that something about a joint or a

laboratory test is unusual or abnormal gives the doctor crucial information. It is important that Patient Partners appreciate this and understand how these terms are used both in this manual and in clinical situations.

The consultation process

There are two parts of a consultation from the doctor’s viewpoint – taking a history and performing an examination. This may be followed by some special tests, such as blood tests or x-rays. When the doctor is confident about the diagnosis he or she will work out a management plan in partnership with the patient. The doctor also needs to tell the patient about:

- What is known about the cause of their problem.

- What, relying on their clinical experience, the doctor expects the course and pattern of the condition will be (although it is important to remember that people are unique and no-one has the crystal ball that will predict exactly what will happen to each individual).

- What treatments are available.

- What the likely benefits and possible side-effects of treatment will be.

- What support will be available from the Healthcare Provider (in the UK this is the NHS) and from local Social Services.

Taking a history describes the interview process in which the patient, with guidance from the doctor, describes the problem and gives other information that will help the doctor understand that problem. From the patient perspective it is better described as giving the history. This training manual, along with your own experience, will enable you to give your history in a way which will teach the doctor and improve his or her ability to take a history for other patients.

The other important component of a consultation is the examination of the musculoskeletal system – the bones, joints and muscles. That is a systematic assessment of the condition of the patient’s joints and how well they are functioning and possible problems with the other tissues of the musculoskeletal system.

These may be done first as a screening assessment to rapidly identify whether there is a musculoskeletal problem and where it is located and is then followed by a full history and examination to evaluate the problem identified.

If the person is already very specific about the problem, then the doctor may just take a full history and perform an examination of that problem. For example, if the person is just complaining of shoulder pain, the doctor may just assess the neck and shoulder. However, he may also do a screening examination to check quickly whether there are any other joints affected or other musculoskeletal problems.

When you are demonstrating how to assess your musculoskeletal problem at a Patient Partner meeting, such as a problem with your knee, you will need to be able to describe the problem in a way that provides all the information that doctors will need to know to help them fully understand your problem. By taking them through your history in this way, and guiding them if they do not seem to know what questions to ask, you will be helping them assess such problems more effectively in the future. It will be much easier for you to do this if you first understand what sort of information they need to know and why. You also need to know the purpose and principles of examining the musculoskeletal system so you can demonstrate the examination effectively. The aim of the next section is to explain this background and the principles involved.

Giving your history

As a Patient Partner you will be able to draw on your own experience to give a personal history to the doctor or other health professional. It is not the role of a Patient Partner to formally teach history taking, but it is quite appropriate for you to guide and prompt doctors if they do not know what to ask, forget to ask about certain items, or ask the wrong sort of question that will miss significant information. They will then learn by experience.

You may find this process easier if you have some understanding of how the ideal consultation can be structured. This will also help you develop the script that describes the history of your problem.

The doctor should initially have a general conversation with the patient, with open remarks such as, “Tell me about your problem”. The doctor should be listening to the patient’s description of his or her problem in his or her own words and at the same time observing the patient’s overall appearance and demeanour; that is assessing whether the patient is troubled or depressed by the condition. The doctor should be watching the patient walk and sit down and seeing whether he or she has problems with movement.

The doctor should then try to explore the patient’s problem by asking about the following:

- What are the symptoms that the patient is experiencing (pain, stiffness, deformity, loss of function etc)?

- The characteristics of these symptoms?

- The site(s), and pattern of these symptoms?

- The time scale over which the symptoms developed and the order in which the symptoms appeared?

- Whether there are any associated symptoms, such as fever, loss of energy, weight loss, rashes etc?

- If there are any interventions, including medicines, that alleviate these symptoms?

- If any factors came before or triggered off these symptoms?

- The impact of these symptoms on the patient’s quality of life?

In addition, the doctor will ask questions about:

- The person’s lifestyle.

- The person’s general health and any other medical conditions they have.

- The person’s past history.

- His or her family history.

Before we consider the history taking further, it is worth spending a few minutes to consider just what the symptoms of arthritis or musculoskeletal conditions are.

Symptoms of musculoskeletal conditions

Musculoskeletal conditions have a number of profound effects on the individual – each affecting different people in different ways.

Common symptoms are:

- Pain, often chronic.

- Loss or limitation of function.

- Stiffness in the spine or limbs.

- Weakness.

- Swelling of a joint.

- Deformity of a joint (see special note).

- Instability (giving way) of a joint.

- Fatigue and malaise (general feeling of being unwell).

As a result the person may have:

- Depression and fear.

- Sleep disturbance.

There may also be other symptoms such as:

- Numbness or tingling in the fingers or toes.

- Mouth ulcers.

- Dry mouth.

- Dry or red eyes.

- Rashes, including psoriasis and sensitivity to sunlight.

- Nodules.

- Indigestion, often related to treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Unusual or excessive diarrhoea.

- Pain or difficulty with urination.

- Weight loss.

- Fever.

A sample of the type of questions that will be asked when the doctor takes a detailed history is summarised in the tables. These tables also include a brief summary of what sort of information the doctor will gain from these questions, which may help you understand why these questions are necessary. These lists are not comprehensive, the doctor will not necessarily ask every one of these questions, and may ask others. These tables are just a guide to help understand the types of questions and their aims.

Special note

As with the terms “abnormality” or “abnormal”, “deformity” has a specific technical meaning in relation to joints or bones. A joint deformity refers to misalignment of the two bones that move against each other in a joint.

A bone deformity suggests an abnormal shape of a bone or bones. It is preferable that the term “finding” is used rather than “abnormality” but many doctors will use the term deformity. As with abnormality, the patient should not be upset or distressed by this term.

| Question about Pain | What this tells the doctor |

| Where is the pain and where does it spread to? Ideally the patients should indicate with their hands exactly where on their bodies the pain is felt and where it is most intense. | The site of the pain tells a lot about what is causing it. Pain may be clearly localised to an anatomical structure, such as the knee, but sometimes it is more diffuse and can be referred from another structure, so that the pain appears a long way from where it originates. For example a problem with the hip sometimes causes pain to be felt in the knee. Generalised pain (pain all over) is usually due to a different set of diseases to those that cause localised pain. |

| What is the pain like? For example, is it sharp, stabbing, shooting, throbbing or dull and aching? How severe is it? Is it an ache or agony? | Pains have different qualities depending on their cause. Shooting pains are usually associated with nerves, aching pains with joints, while throbbing pains may be due to inflammation. |

| Is there a pattern to how the pain has developed or spread?

The doctor needs to know how the patient has arrived at the present situation. |

Some diseases have a specific pattern of pain. For example, gout pain starts as a pricking in the big toe which builds into a severe burning pain over a day or two. Rheumatoid arthritis follows a gradual course, starting typically in both hands and wrists, and then both feet. |

| Was there any injury or change of use (repetitive or unusual) before the onset of pain? | Many episodes of musculoskeletal pain follow an injury, such as whiplash strain and neck pain. Suddenly doing repetitive activities can also cause musculoskeletal pain. |

| Do you have pain when you are at rest or at night? | Conditions such as osteoarthritis are more painful when the joint is used, whereas inflammatory joint pain, such as that of rheumatoid arthritis, is present at rest and is usually worse in the morning and/or evening. Back pain due to mechanical problems is better when resting but inflammatory problems cause pain at night. |

| Does anything make the pain worse? | Mechanical pain and the pain

of osteoarthritis are often worse with physical activity. Being able to move a joint without pain may show that there is not a problem of the joint itself and the pain may be referred. |

| Does anything improve the pain? Do any activities or interventions, including medication, relieve the pain? | Rest may relieve osteoarthritis pain but has little effect on inflammatory pain. Exercise improves inflammatory low back pain. Inflammatory pain responds well to anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Does any other problem accompany the pain? | Pain may prevent sleep or may be causing depression.

|

| How does the pain affect your life?For example, does the pain prevent you doing anything? | Pain may prevent people carrying out normal daily activities and affect their quality of life. |

| Questions about loss of function | What this tells the doctor |

| Are you having any difficulties with any activities that you could previously do quite easily? | Difficulty with specific activities can point to which joint is affected by the patient’s condition. |

| Do you have any difficulties washing and dressing? | This is a good measure of function of the lower limbs. |

| Do you have any difficulties going up and down stairs? | This is a good measure of function of the lower limbs. |

| Do you have any difficulties with activities in the home because of this problem? | Musculoskeletal problems often affect the ability to carry out domestic activities. |

| Do you have any difficulties with your work because of this problem? | Musculoskeletal problems often affect the ability to carry out employment activities. |

| Do you have any difficulty with leisure activities because of this problem? | Musculoskeletal problems often prevent people participating in activities such as walking for pleasure or playing sports. |

| Questions about stiffness | What this tells the doctor |

| Are you stiff at all? Which parts are affected? Is it the joints, muscles, back or generalised? | Stiffness also means different things to different people and what is being described needs to be clarified.

Generalised stiffness can occur after a long car journey or the day after exercise. This is quite normal and occurs more often as people age. Some musculoskeletal conditions can also cause stiffness. Stiffness of joints and marked morning stiffness of the back point to a specific problem. |

| When during the day is the joint most stiff? | Inflammatory joint disorders cause prolonged morning stiffness and osteoarthritis is associated with short-lived stiffness after inactivity such as sitting in a chair for a few hours. |

| How long does the stiffness last? | The time the stiffness lasts can tell a lot about the severity of the arthritis. |

| Does anything make the stiffness worse? | Short-lasting, but severe, stiffness after inactivity is typical of osteoarthritis. |

| Does anything make the stiffness better? | The stiffness of osteoarthritis may be overcome by gentle use of the joint but this is often not the case for rheumatoid arthritis. Stiffness of the back due to inflammation improves with exercise. |

| Questions about swelling and joint deformity | What this tells the doctor |

| Do you have any swelling of the joints or elsewhere? | Swelling can be of the joint or periarticular structures such as a bursa or tendon sheaths. Hard swellings called nodules can develop in RA. |

| Did the swelling or changes appear rapidly or slowly? Is it painful? | This will tell the doctor something about how severe the condition is and how it is progressing. |

| Did the joint swelling or changes follow an injury? | The doctor needs to know whether the swelling is a short-term response to a recent injury which is not an arthritic condition or whether arthritis is developing after an injury. |

| Do the problems come and go? | Rheumatoid arthritis and similar conditions can have flare-ups and quiet periods, while other types of arthritis may be progressive. |

| Is the joint gradually getting bigger? | Gradual enlargement of a joint suggests a progressive condition. |

| Questions about the timeframe of the disorder and other relevant questions | What this tells the doctor |

| When did the problem start and the pattern that has developed and over what time? | All these questions help the doctor differentiate between the different causes of musculoskeletal problems. |

| Where and how has the problem spread? | |

| What associated symptoms have developed and when did they occur? | |

| Did you have an injury sprain or strain of the affected joint or region in the past? | |

| Do you have loss of strength? | This is asking about a loss of muscle power, not loss of energy. Generalised weakness may be a sign of muscle disorders such as polymyositis. Weakness in specific limbs will have a specific cause, maybe a nerve problem that needs identifying. |

| How do you feel generally? | Inflammatory conditions such as RA are often accompanied by feelings of malaise. Generalised illness that can affect bones and joints may cause people to feel unwell. |

| Do you suffer from tiredness or fatigue? | Fatigue accompanies many rheumatic disorders, such as RA, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and fibromyalgia. People with these conditions are often able to function for several hours but then become overwhelmed by fatigue. |

| Is your sleep disturbed? | Pain or discomfort can affect sleep, contributing to fatigue and depression. Pain at night is an important clue for certain types of arthritis. |

| How do you feel upon waking in the morning? | Morning stiffness is indicative of certain types of arthritis. Waking unrefreshed may point to fibromyalgia. |

It is well recognised that some of these symptoms are difficult to describe clearly.

For example, what is an unacceptable degree of pain to one person may be perceived as a slight pain to another and some perceive admitting to pain as “making a fuss”. To overcome this problem the doctor should always watch patients for signs of pain (wincing or grimacing) during examination and ask the patient to mention any pain felt. It also helps if the doctors ask questions that suggest words to describe the pain (see table) and they may also suggest to the patient activities that make the pain worse or better. Another way of conveying the severity of pain is to ask a patient what it stops him or her doing.

If a person reports “fatigue”, it is important that the doctor understands the nature of the tiredness. The patient may be feeling tired because pain is stopping him or her sleep, or maybe the patient is depressed by the illness; on the other hand, fatigue may be a feature of the illness which points to inflammatory (rheumatoid arthritis type) diseases rather than the “wear and tear” (osteoarthritis type) illness.

If a person reports “fatigue”, it is important that the doctor understands the nature of the tiredness. The patient may be feeling tired because pain is stopping him or her sleep, or maybe the patient is depressed by the illness; on the other hand, fatigue may be a feature of the illness which points to inflammatory (rheumatoid arthritis type) diseases rather than the “wear and tear” (osteoarthritis type) illness.

The detailed questions are also necessary to make quite sure that the patient’s problem is truly musculoskeletal. There are illnesses that may look similar to a musculoskeletal condition but which need quite different treatment.

Special note

Many doctors are not fully aware how pervasive arthritis and other chronic musculoskeletal conditions can be on a person’s everyday life. For some people their condition impacts constantly throughout the day.

As a Patient Partner you have the direct experience of the impact of a musculoskeletal condition that can help inform the healthcare professionals in a way that no text book can.

Impact of symptoms

It is important that the doctor knows how the symptoms are impacting on the patient’s daily life.

The doctor should ask several questions about how the condition is affecting the patient and their quality of life. The doctor should also ask questions so as to understand the situation of the patient, such as his or her support by family and friends, the home environment, their work and the everyday activities they need or are expected to be able to carry out. The information will be clearer and more useful if it is gathered in an organised rather than a haphazard way. It is important that the doctor understands how the musculoskeletal problem limits activities and restricts participation.

The activities affected can be considered under four headings:

- Self care e.g. washing, dressing, going to the toilet, feeding.

- Domestic care e.g. cooking, cleaning, laundry, shopping.

- Work e.g. standing, sitting, typing.

- Leisure e.g. playing sports, walking the dog, going out for meals.

People with musculoskeletal conditions may also find that (when relevant) their problem is affecting their sexual relationship with their partner. This could also be mentioned if you feel comfortable talking about this in your demonstration.

You should therefore describe the impact your condition has on you in these terms to ensure the health professional fully appreciates how it affects you.

Many doctors are not fully aware how pervasive arthritis and other chronic musculoskeletal conditions can be on a person’s everyday life. For some people their condition impacts constantly throughout the day.

As a Patient Partner you have the direct experience of the impact of a musculoskeletal condition that can help inform the healthcare professionals in a way that no text book can.

Principles of examination

The examination of the musculoskeletal system is to answer important questions that, together with the history, should enable a diagnosis to be made.

These questions are:

- Is the patient’s musculoskeletal system normal?

- If there is an abnormality?

- What structures are involved?

- What is the cause?

- Inflammation?

- Damage?

- Mechanical problems?

- What is the pattern of distribution?

- Is it one-sided or does it affect both sides of the body

- What other features are there that may help assess the problem?

In order to define the nature of the abnormality the doctor will be looking for:

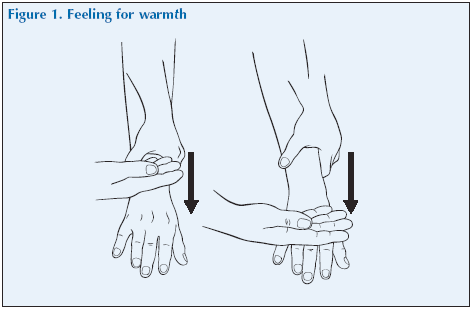

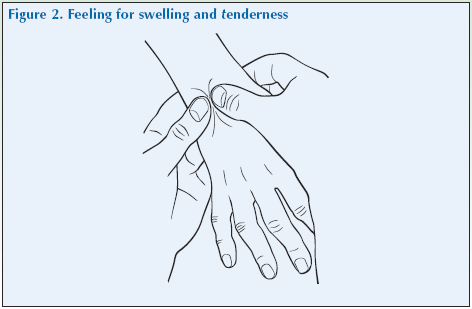

Inflammation of the joint. It is important to distinguish between inflammatory types of arthritis and non-inflammatory conditions. In general terms the signs of inflammation are: warmth, swelling, and tenderness.

Warmth which can be elicited by lightly stroking the back of the hand starting at a normal area and moving over the joint. This method is suitable for testing medium and large joints such as knee, ankle or wrist, but you cannot feel the temperature of deep seated joints like the hip.

Swelling of a joint. This may be due to swelling of bone, swelling soft tissue such as the lining of the joint (synovitis) or the accumulation of fluid (an effusion) in a joint, or a combination of these. One purpose of examining the swelling is to determine what is the cause and there are ways of doing this which you will learn about. Sometimes x-rays or other tests are also done to establish the cause.

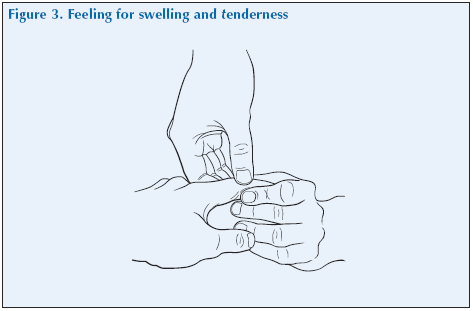

Tenderness. This is assessed by gentle palpation or squeezing to test which structures are tender. Any structure of the musculoskeletal system can be tender. Tenderness can be a feature of inflammation but muscles which are in spasm for other reasons can be tender.

Redness can be seen over very inflamed joints such as in gout or with infection.

Crepitus, which is an audible sensation that can also be felt by the examiner, results from the movement of one rough surface over another. The roughness may arise from OA when it makes a sound that differs from that of a normal joint.

Damage may be irreversible damage from past inflammation, recognised by deformity of the joint and permanent loss of normal range of movement.

Mechanical problems can include tears of ligaments, or prolapsed discs in the spine (slipped disc). These are identified by a painful restriction of movement of the joint in the absence of inflammation.

The range of joint motion (ROM) will reveal problems. Joints that can move further than the average show hypermobility (hyper- means more than usual; hypo means less than usual). Joint movement is usually diminished by inflammation or by irreversible damage to the joint structures by disease. Progressive diseases are accompanied by progressive loss of movement. If movement is lost completely it is known as ankylosis.

Other features are signs of systemic illness and skin signs. Skin signs can include nodules that suggest RA.

All these observations are vital to diagnosis and there is a systematic way of obtaining this information. The following sections will consider different joints and will all use this system for examining a joint and its surrounding tissue. This system may be summarised as:

| Look (inspect) – looking at the patient and the joint at rest and during movement | Many abnormalities can be noted by careful observation. The doctor should look at the way the person moves, performs activities and the posture adopted.

Any deformity or swelling should be noted. The skin overlying the affected region should be looked at. The muscle bulk should be looked at to see if there is any loss (wasting). |

| Feel (palpate) – feeling the joint | The joint should be felt for warmth and tenderness. Any swelling should be characterised – exactly where is it, is it tender, is it fluid, soft tissue or bone? |

| Move – establishing the range of motion of the joint by both active, passive and resisted movement and looking at how the function of the joint is affected | Abnormality of movement can be assessed, if the problem only affects one side, by comparing the abnormal joint with the other side. The pattern of loss of movement or the effect that movements have on pain can help identify the cause. |

| Stress – carry out physical tests on the joint by getting the patient to move against a resistance (often the examiner’s hand) | Testing if stressing a joint causes pain or if it is unstable can help identify the problem. |

| Listen | Listen for sounds of crepitus when the joint is moving. |

| Special tests – consider any other investigations that allow diagnosis of specific conditions | There are many special tests used when examining the musculoskeletal system but only the most important ones will be considered here. |

These concepts are outlined in greater detail in the joint examination script.

Screening assessment

As we have said already, a screening assessment can establish whether there is actually a musculoskeletal problem, and locate where this problem is before a more detailed assessment. There is no point wasting time fully examining a person’s legs if the only problem is pain in his or her hand. It is also important to differentiate local from generalised problems.

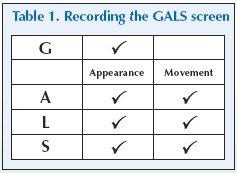

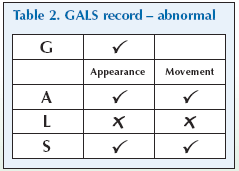

This screening assessment is based on a validated and widely used method which assesses a person’s

- Gait

- Arms

- Legs

- Spine.

The doctor needs to ask questions related to, and then examine, all these aspects of the patient.

The doctor will ask:

- Do you suffer any pain or stiffness in your arms, or legs, neck, or back?

- Do you have any difficulty with activities such as washing and dressing or in going up or down stairs?

- Do you have any swelling of your joints?

- How is your general health (i.e. is there any systemic illness)?

Dressing without difficulty – including putting on tights or socks and shoes, doing up buttons or tying a tie – is a complex use of the joints and utilises subtle movements of both the upper limbs (shoulders, elbows wrists and hands) and lower limbs (hip, knee, ankle and feet). Washing also needs good function of the arms and hands. Coping with stairs needs good function of the legs. These questions therefore give a good, simple and quick indicator of musculoskeletal health.

The doctor will then perform a rapid screen of all joints to locate the site of the problems. These are given in the examination script. The movements used in the GALS are the first to show evidence of disease so it is a sensitive test of early problems.

A musculoskeletal problem is very unlikely if the person has no symptoms and if the appearance of the muscles and joints is normal and the joints move normally.