Introduction: The Knee

The knee is the largest and most complicated joint in the body. It depends for stability on internal soft tissue structures such as the cruciate ligaments and on external soft tissues of the capsule and capsular ligaments. This joint is the most vulnerable to injury, loose bodies and several arthritic conditions. It is very important for mobility.

Anatomy of the the knee

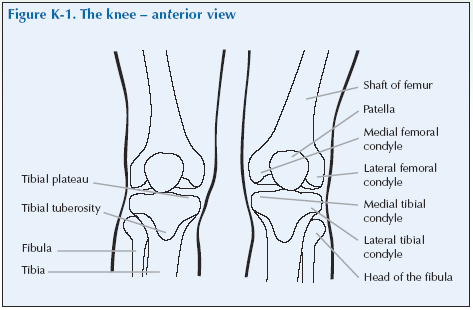

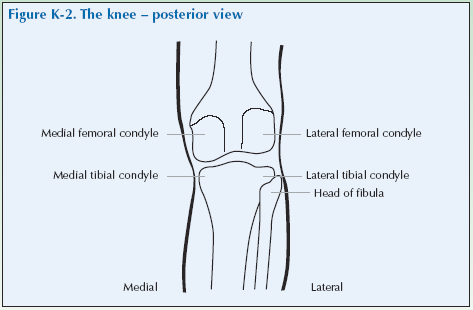

The knee articulates (or joins) the bones of the leg; the femur (or thigh bone) is superior to the knee, the fibula (or small bone of the lower leg) is inferior and lateral to the knee and the tibia (or large bone of the lower leg) is inferior and medial to the knee. The patella or kneecap is located over the anterior section of the knee.

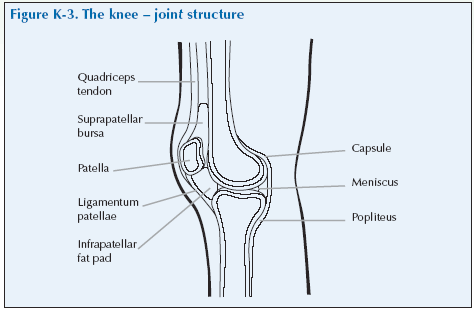

The knee contains several bursae, the most significant of which are the prepatellar bursa located over the patella, the infrapatella bursa located below the patella, and the suprapatella pouch located anteriorly and slightly superior to the patella. The quadricep muscles are anterior and superior to the knee joint.

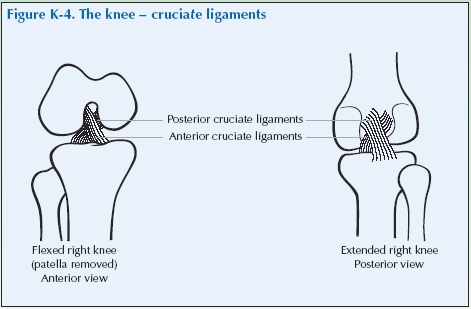

The knee is stabilised by the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments at the back of the knee and the medial and lateral collateral ligaments at the side of the knee. (Cruciate means like a “cross” and these two ligaments are arranged in a cross formation to provide stability to the knee.) The anterior cruciate ligament prevents a posterior displacement of the femur on the tibia, and the posterior cruciate ligament prevents an anterior displacement of the femur on the tibia.

The collateral ligaments prevent the knee from rotating when it is extended; they extend down the medial and lateral aspects of the knee. The patella is secured by the patellar ligament and muscles, which allow the kneecap some movement. The popliteal fossa is the space formed by the soft tissues at the posterior aspect of the knee.

Problems of the knee

Problems of the knee may present as:

- Pain – which may be constant or intermittent, or precipitated by activities such as sport or walking up or downhill.

- Swelling.

- Stiffness or limited movement.

- A hot, red and swollen joint.

- Crepitation.

- Locking.

- Giving way.

There are several common causes of knee problems. In young adults trauma and sports injuries are the most common causes. In older people, osteoarthritis is the most common cause.

Articular causes[su_table]

| Osteoarthritis | Patellofemoral joint

Knee joint |

| Inflammatory arthritides | Rheumatoid arthritis

Spondyloarthropathy Crystal arthritis Infection |

| Mechanical | Meniscus problems |

[/su_table]

Periarticular problems[su_table]

| Bursitis | Prepatellar bursitis, Anserine bursitis |

| Tendinitus | Tibial tendinitus, Adductor insertion tendinitus |

| Popliteal cyst | Also known as Baker’s cyst |

| Ligament problems | Cruciate ligament, Collateral ligament |

[/su_table]

Pain and crepitation suggests roughening of the patellar undersurface that articulates with the femur.

Note: crepitation alone, without pain, is not significant.

Giving a history of knee problems

Invite the doctor to carry out a consultation by first asking you about your history related to the experience you have of your condition. This will then be followed by the physical examination.

The doctor should first ask you ‘What is the problem?’ and you should give a short response describing your symptoms and their effect on your quality of life.

Develop a script based on your own experience. You may still have the symptoms or you may be describing an episode you have had as if it were still present.

Describe as fully as you can your own symptoms, including where in and around the knee you feel/felt pain or discomfort. Say if you have any stiffness, swelling or other symptoms. Mention how the problem is having/had an impact on your daily life, your work or your sleep.

Remember to describe how your condition affects/affected your quality of life. Consider self care (e.g. ability to wash, dress, toilet and feed), domestic care (e.g. ability to cook, clean, launder, shop), work (e.g. ability to stand, sit, type), leisure (e.g. ability to play sports, walk, go out for meals). Explain about the way it limits/limited your activities and restricts/restricted your participation in normal life.

Do not tell him everything spontaneously – just the important part. He will then need to ask further questions to fully characterise your problem. Develop a set of answers with your trainer to the following points. Prompt them if they omit important questions.

Pain is usually present and questions should establish:

- How the pain started and developed.

- The nature of the pain.

- The exact distribution of the pain.

- Whether the pain has increased or decreased over time.

- Whether it affects sleep.

- Whether anything exacerbates or relieves the pain. Stiffness may be a symptom and questions should establish:

- If you are stiff at all?

- When it is worse?

- What improves it?

Swelling may be a symptom and questions should establish:

- If you have noticed any swelling and where.

- If it is always present.

- If it is painful or tender.

- If it is increasing.

They need to ask about the pattern of all the symptoms – where they started and if they have spread anywhere.

You may prompt the doctor (if you have not already told them) to make sure that they include the following information:

- Your age, occupation and hobbies.

- Your general health.

- Your past medical history.

- Whether you have injured or strained your knee.

- Whether the knee locks or gives way.

- Whether there is any impairment of function and how this impacts on your daily activities and quality of life.

- Knee problems typically cause difficulty in walking, walking up or down slopes, rising from a seated position or kneeling down.

- Whether you have had previous treatment and if so whether it was successful.

The effect of any problem depends on your personal circumstances. The doctor needs to know about what you need to do in the home, at work, your leisure interests and your expectations.

You may have symptoms affecting other parts of your musculoskeletal system. You may prompt the doctor to ensure he has asked whether you have any other problems affecting your muscles, joints, neck or back.

You may go into further details about how your problem affects your life and the treatment you have received at the end of the session when discussing the findings.

Example of a Script

You should develop something like this, based on your own story. First you need to ask me:

“What is your problem?”

“I have worsening pain in my knee when I walk, and now even when I am sitting in a chair. It has given way a few times, and is stopping me going for a walk and I am getting unfit.”

You should then respond to questions, guiding and prompting the doctor through the information as listed above.

Knee Examination Script

Describe the examination to the doctor using the anatomical and directional terms you have learnt. You can use your knowledge of anatomy best when the doctor is feeling the joint and periarticular structures.

“I would now like to invite you to find out a little bit more about my problems, by role play, using me as your patient and examining me.”

Look

Standing

With the patient standing, look from the front and back for any malalignment.

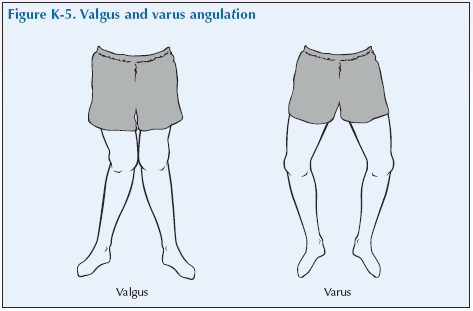

Valgus angulation (knock-knees) (most common in RA)

Varus angulation (bow-legs) (most common in OA)

Look at the front of the thigh for any wasting of the quadricep muscles with loss of muscle bulk.

Also while the patient is standing with both knees fully extended, look behind the knee for any fluid accumulation. This could indicate a popliteal (Baker’s) cyst, a fluid filled protrusion of the synovial membrane into the popliteal fossa in a knee affected by OA. If there is a swelling, palpate whilst the patient is still standing to confirm that it is fluid. A popliteal cyst is best palpated when the knee is fully extended as otherwise it can remain undetected in the joint space when the knee is flexed.

Lying down

Now with the patient lying, look for redness and swelling of the joint. You may see swelling on either side of the patella (loss of the normal hollows around the patella) and around the suprapatellar pouch (the horseshoe-shaped area above the patella which is part of the joint space).

What do you see?

Feel

Lying down

With the patient lying and the leg outstretched feel for heat generally, palpate for swelling and tenderness of the knee joint and around all bursae including the suprapatellar pouch which is additionally checked for synovial thickening and effusions.

Start above the superior border of the patella (well above the pouch) and feel the soft tissues between your thumb and fingers. Move your hand distally in progressive steps, trying to identify the pouch. Swelling above and adjacent to the patella suggests synovial thickening or effusion in the knee joint.

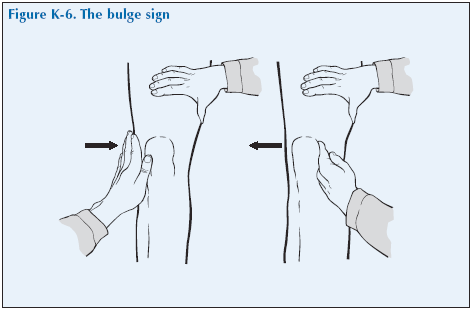

If you suspect a small amount of fluid around the knee test by:

The bulge sign (for minor effusions). With the knee closest to you extended, squeeze the area above the knee, applying firm pressure on the suprapatellar pouch, and pushing downward toward the patella. With the other hand, stroke towards the patella on the medial aspect of the knee two to three times, displacing or “milking” fluid under the patella and applying firm pressure to force fluid towards the lateral area. Maintaining the grip on the superior aspect of the knee, remove your hand from the medial aspect of the knee and quickly press firmly against the lateral margin of the patella. A fluid wave or bulge on the medial side between the patella and femur confirms an effusion.

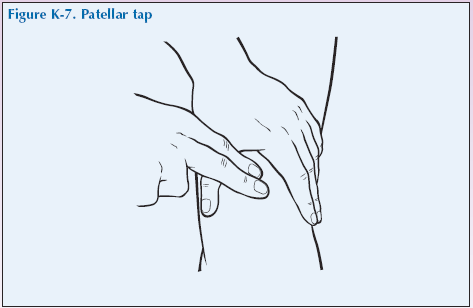

Tapping the patella (for large effusions). Push firmly down on the suprapatellar pouch with the palm of one hand while squeezing the lateral side of the knee with the thumb and fingers. With the other hand, encircle the inferior aspect of the knee, pressing toward the patellar. With your dominant index finger, firmly “ballotte” or quickly tap the patella against the femur to see if it bounces, which it will do if there is fluid trapped beneath it. Sometimes a clicking sound is heard. Watch for fluid returning to the suprapatella pouch as the hand is removed.

Feel for tenderness or a popliteal cyst by gently putting the fingers of both hands into the popliteal fossa and gradually exerting more force.

Feel the margin of the joint. With the knee semiflexed at about 90°, palpate along the sides of the patella and then the rim of the knee. Note where it is painful as this may be a sign of meniscal injury. Note any irregular bony ridges along the joint margins, which may be felt in OA. Then feel specifically for the medial and lateral collateral ligaments and their insertions.

What do you feel?

Move

Lying down.

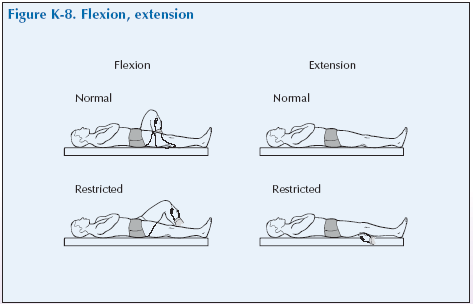

Passive Range of Motion (ROM)

Ask the patient to lie supine. Move the knee by holding the leg midcalf with one hand and holding the patella with the other hand.

Flexion – Bend the knee, bringing heel to buttocks.

Extension – Straighten the leg.

Movement against resistance

Test the quadriceps power with the patient lying with the leg extended. Place one hand proximal to the patella and feel the muscle and assess its strength when you ask them to lift the leg against your pressure.

Wasting of the quadriceps can also be assessed by measure the quadriceps by measuring the circumference of the thigh will also point to unilateral wasting. Measure 3” or 7.5 cm above the superior pole of the patella and mark. Measure the circumference of the quads bilaterally. This measurement should be used over time to track wasting or increase in muscle bulk.

What have you found?

Stress

Ligament Stability Tests

Assessing ligament stability is important. The following are examples of tests to determine stability:

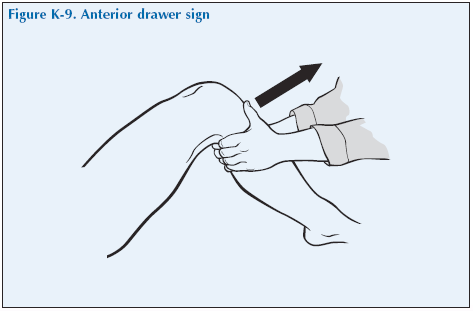

Cruciate Ligament Stability Test – Anterior drawer sign

With the patient supine, hips and knees flexed and feet flat on the examining table (if possible) stabilize the distal portion of the leg with one hand and place the other hand behind the knee. Pull on the proximal posterior aspect of the tibia, drawing the tibia forward. Observe if the tibia slides forward (like a drawer) from under the femur. Compare the degree of forward movement with that of the opposite knee. A few degrees of forward movement are normal if present equally on the opposite side.

A forward motion showing the contours of the upper tibia is a positive anterior drawer sign which suggests involvement of the anterior cruciate ligament.

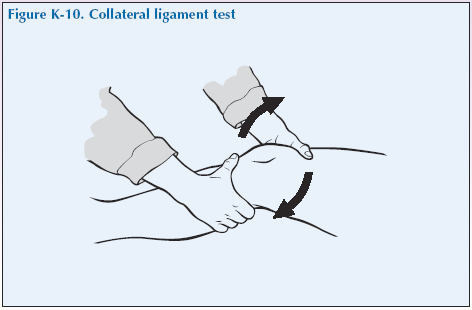

Collateral Ligament Stability Test

Ask the patient to extend the knee. Stabilise the joint margin with one hand under the knee, allowing the knees to relax and flex very slightly into your hand. The other hand should hold the distal aspect of the lower leg (just above the ankle), raise the foot slightly and rock the distal portion of the leg medially and laterally. There should be little or no movement of the proximal aspects of the tibia and fibula.

Listen

During all tests listen for signs of crepitus.

Special tests

No additional test for the knee are needed routinely.

“We have now come to the end of this mock consultation. You should have learned quite a bit about my condition from taking my history and examining my joints, however, I would be happy to provide you with a bit more detail about the progress of my condition and how it affects my life, if you would find this useful.”

[Please give a brief description of your condition:

- When and how it started.

- Physical and psychological affects on you.

- Treatments offered.

- How your condition progressed.

- How this affected your life: Home, education, work, leisure, ability to travel, relationships etc.]

“Does anyone have any further questions?”

“Thank you again for attending this session. I hope you have found it useful.”