Anatomy of the back

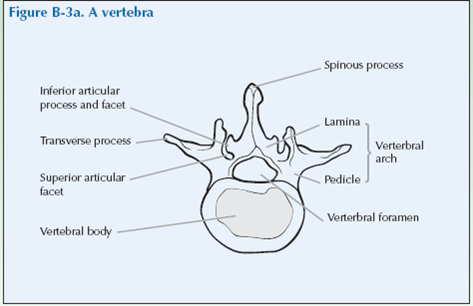

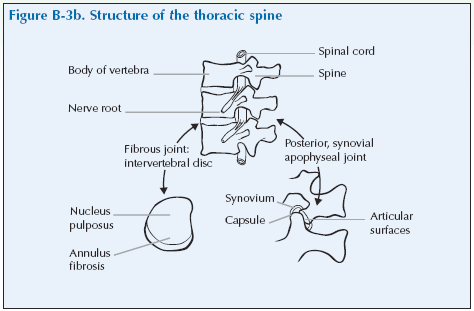

The spinal column or backbone is comprised of a column of small bones or vertebrae (singular vertebra) which are connected by cartilaginous joints.

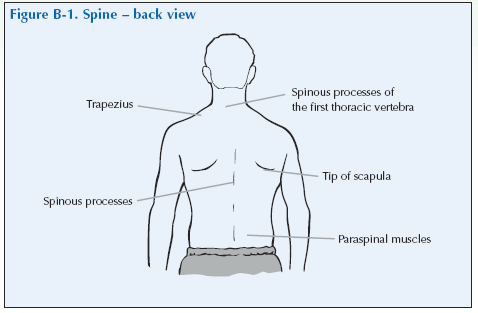

There are seven cervical vertebrae in the neck, twelve thoracic vertebra in the chest (to which the ribs are attached) five lumbar vertebrae in the lower back, and five sacral vertebrae. The sacral vertebrae are fused to form the sacrum which comprises part of the pelvic girdle and the coccyx is the final part of the spine. The spinous processes of the vertebrae are small bony projections that protrude posteriorly and can easily be palpated along the midline of the back.

The vertebrae are numbered sequentially from skull to coccyx using a letter to denote the region of the spine and the numbering starts again at 1 for each new region. So cervical vertebrae are C1-C7. C7 is next to T1 and T12 is next to L1.

Each pair of adjacent vertebrae is connected by facet joints (also called apophyseal joints), which both stabilise the vertebral column and allow movement in it (Facet just means a small flat surface). Each vertebra has two sets of facet joints. There is one joint on each side (right and left). Facet joints are hinge-like and link the vertebrae together. They are located at the back of the spine (posterior).

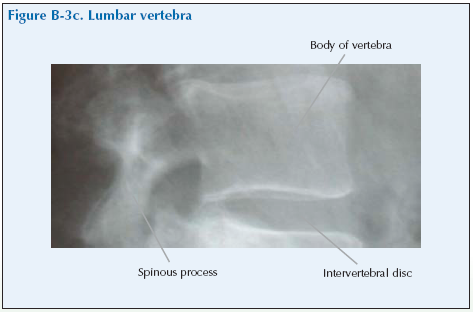

The vertebrae (except between C1 and C2 in the neck) are separated by intervertebral discs of a jelly-like substance held in a fibrous sheath. Each vertebra and disc can move only a limited amount but the net effect of several vertebrae moving is to allow considerable flexibility of the spine without reducing stability. The amount of movement in lateral flexion, flexion extension and rotation varies at different levels of the spine.

The vertebrae are stabilised by two major ligaments. The anterior longitudinal ligament is a broad, strong band of fibres extending along the front and sides of the vertebrae and the posterior longitudinal ligament extends along the posterior surface.

The spine provides a bony protective sheath for the spinal cord which is a collection of nerve cells and a bundle of nerves that connect all parts of the body with the brain. The spinal cord ends at the second lumbar vertebra but large nerves descend vertically from the spinal cord through the lumbar and sacral regions in a structure called the cauda equina. The major nerves of the body leave the spinal cord at different levels of the spine to take information to and from the brain. There are 31 pairs of spinal nerves that leave the spinal cord passing out from the vertebral canal through the spaces (foramina) between the arches of the vertebrae. There are also lumbar, sacral and coccygeal spinal nerves that pass from the spinal cord via the cauda equina and leave the vertebral column in the lumbar, sacral and coccygeal regions.

These nerves can become damaged, squashed or trapped giving rise to symptoms down the arms or in the hands. These may be anaesthesia (loss of feeling) parasthesia (pins and needles) pain or weakness of the relevant muscle. Such nerve damage is commonly seen in prolapsed intervertebral discs (‘slipped disc’) when the distribution of the sensory or motor effects enables the exact site of the damaged disc to be predicted.

The pain or loss of sensation will be felt in the distribution of that nerve (the parts of the body supplied by that nerve) or may be referred to other body regions. The weakness will be of muscles supplied by that nerve.

Two important nerves in this context are the sciatic nerve, the major nerve of the leg and the femoral nerve, which supplies the thigh muscles.

Back pain

Back pain is a very common and troublesome complaint, affecting around 70% of the population. Back pain can be caused by systemic disease, or sepsis (infection). There are also structural conditions such as facet joint arthritis, or prolapsed intervertebral discs.

Causes of back pain

[su_table]

| Mechanical/degenerative | Disc degeneration

Apophyseal (facet) joint OA Back strain Non-specific causes |

| Inflammatory | Spondyloarthropathies |

| Metabolic | Osteoporosis with fracture |

| Infection | Infection is an uncommon but important cause. This should always be thought of by the doctor as early diagnosis and treatment is necessary |

| Tumours | Tumours are an uncommon but important cause. This should always be thought of by the doctor as early diagnosis and treatment is necessary |

| Disc problems | Herniated disc

Sciatica |

[/su_table]

Sciatica is due to compression of the sciatic nerve that supplies the leg and is accompanied by pain running down the back of the leg from buttock to ankle. Prolonged sciatica can lead to muscle weakness.

Back strain due to lifting or twisting is a common cause of back pain in younger people and is usually self-limiting.

Degeneration of the intervertebral discs and OA of the apophyseal (facet) joints is extremely common with ageing and it is often without symptoms. In the majority of cases of back pain in older people there are no obvious causes apart from the degeneration that occurs with age. Sometimes, obesity or excessive use of the spine by manual workers may be contributory factors.

There is a group of inflammatory rheumatological conditions that involve the spine, sacroiliac joints, and peripheral joints, called the spondyloarthropathies. These include ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, enteropathic arthritis and undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy.

Unlike mechanical back pain, which gets worse with physical activity and is usually more pronounced at the end of the day, inflammatory back pain is usually worse after periods of inactivity and in the early morning. Severely affected patients may wake from sleep in the early hours and be unable to lie comfortably.

Giving a history of spinal problems

Invite the doctor to carry out a consultation by first asking you about your history related to the experience you have of your condition. This will then be followed by the physical examination.

The doctor should first ask you ‘What is the problem?’ and you should give a short response describing your symptoms and their effect on your quality of life.

Develop a script based on your own experience. You may still have the symptoms or you may be describing an episode you have had as if it were still present.

Describe as fully as you can your own symptoms, including where in the back or elsewhere you feel/felt pain or discomfort. The pain often spreads into the buttock and leg.

Describe whether you have/had any tingling in your legs and/or feet. Say if you have any stiffness, swelling or other symptoms. Mention how the problem is having/had an impact on your daily life, your work or your sleep.

Remember to describe how your condition affects/affected your quality of life. Consider self care (e.g. ability to wash, dress, toilet and feed), domestic care (e.g. ability to cook, clean, launder, shop), work (e.g. ability to stand, sit, type), leisure (e.g. ability to play sports, walk, go out for meals). Explain about the way it limits/limited your activities and restricts/restricted your participation in normal life.

Do not tell him everything spontaneously – just the important part. He will then need to ask further questions to fully characterise your problem. Develop a set of answers with your trainer to the following points. Prompt them if they omit important questions.

Pain is usually present and questions should establish:

- How the pain started and developed.

- The nature of the pain.

- The exact distribution of the pain.

- Whether the pain has increased or decreased over time.

- Whether it affects sleep.

- Whether anything exacerbates or relieves the pain. Stiffness may be a symptom and questions should establish:

- If you are stiff at all?

- When it is worse?

- What improves it?

Swelling may be a symptom and questions should establish:

- If you have noticed any swelling and where.

- If it is always present.

- If it is painful or tender.

- If it is increasing.

They need to ask about the pattern of all the symptoms – where they started and if they have spread anywhere.

You may prompt the doctor (if you have not already told them) to make sure that they include the following information:

- Your age, occupation and hobbies.

- Whether you have injured or strained your back.

- Your general health and whether you have been feeling ill, lost weight or have had a fever – this is to make sure that some uncommon but serious causes of back pain are not missed.

- Your past medical history.

- Whether you have any symptoms such as tingling, numbness or weakness in your legs.

- Back problems typically cause difficulty with a lot of activities that involve bending, lifting, carrying, prolonged standing or sitting.

- Whether you have had previous treatment and if so whether it was successful.

The effect of any problem depends on your personal circumstances. The doctor needs to know about what you need to do in the home, at work, your leisure interests and your expectations.

You may have symptoms affecting other parts of your musculoskeletal system. You may prompt the doctor to ensure he has asked whether you have any other problems affecting your muscles, joints, neck or back.

You may go into further details about how your problem affects your life and the treatment you have received at the end of the session when discussing the findings.

Example of a Script

You should develop something like this, based on your own story. First you need to ask me:

“What is your problem?”

“I have had back pain intermitently for five years and this episode started a month ago following gardening. It is at the bottom of my back and also my left buttock. It stops me standing for any period of time and I cannot lift anything heavy.”

You should then respond to questions, guiding and prompting the doctor through the information as listed above.

Spine Examination Script

Describe the examination to the doctor using the anatomical and directional terms you have learnt. You can use your knowledge of anatomy best when the doctor is feeling the joint and periarticular structures.

“I would now like to invite you to find out a little bit more about my problems, by role play, using me as your patient and examining me.”

Look

Standing

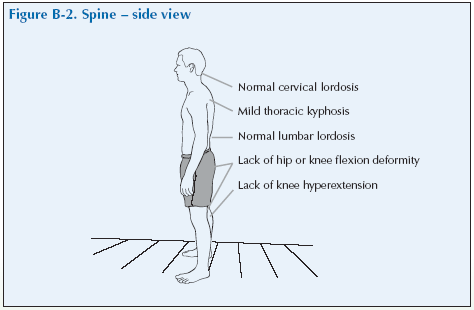

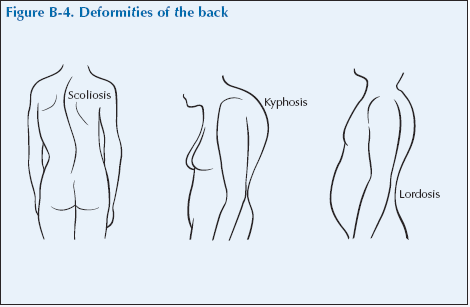

Inspect the patient’s upright posture from the front, side and back. Note the alignment of the spine and assess whether there are any postural defects such as scoliosis, kyphosis or lordosis. Place fingers lightly on the shoulders and iliac crest to assess alignment of the shoulders and hips.

Look for muscle wasting, limb shortening, swelling or deformity.

What do you see?

Feel

Standing

Facing the patient’s back, gently but firmly tap the spinous processes with your index and middle fingers or use the index and/or middle finger to feel for tenderness over a spinous process which would indicate a local lesion at that site.

Diffuse lumbar tenderness is usually not significant.

Feel the paraspinal muscles approximately 2.5 cm (1”) on either side of the spinous processes for signs of tenderness. Using a circular motion keep the fingers in contact with the skin so as not to miss any findings.

What do you feel?

Move

Standing

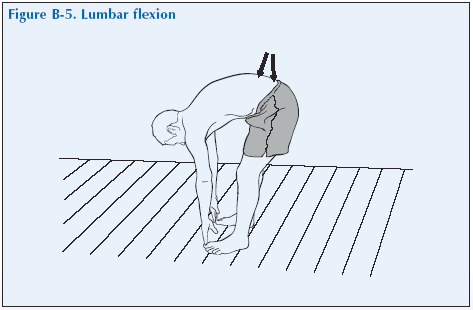

Flexion and hyperflexion You can assess lumbar flexion by asking the patient to stand in the erect posture with their back towards you and then to bend forwards with knees fully extended as if trying to touch their toes. Note the range of movement by how far the finger tips are from the floor, the presence of spasm of muscles, pain on movement, deviation to one side or another (sciatic scoliosis) or the induction of sciatica (indicative of nerve root compression). Look from the side as well to see if the spine is making a smooth arch.

If the patient does not have any limitation in the previous test – ask the patient while in this position, to place their hands flat on the floor. The ability to do so indicates hypermobility syndrome.

When they are trying to touch the ground, put the second and third fingers of one hand on the lower lumbar spinous processes and see how the fingers close up when the patient stands upright. This is a measure of movement of the lumbar spine.

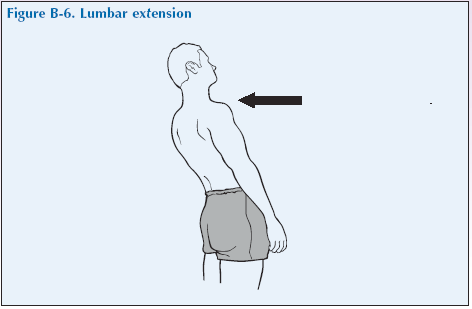

Lumbar extension

Stand behind the patient with his or her back to you and ask him or her to bend backwards trying to arch his or her back as much as possible. The normal angle is 30°. Restricted range denotes spinal problems.

Pain on extension may indicate facet joint syndrome, but is also seen in cases of herniated discs.

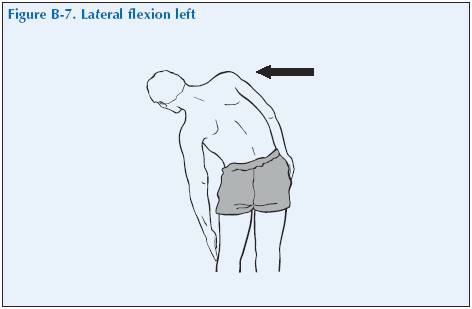

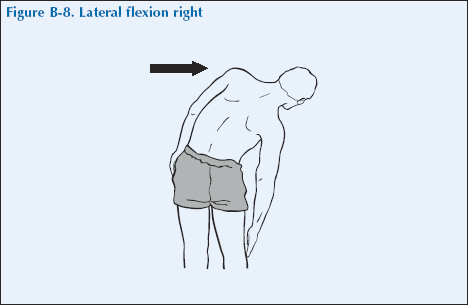

Lateral flexion

Ask the patient to bend to the right and then to the left as if trying to edge his/her fingers as far as the knee. Usually the finger tips should reach as far as the middle of the thigh. Reduction of lateral flexion is typically seen in ankylosing spondylitis but is characteristically relatively well preserved in mechanical low back pain and disc prolapse.

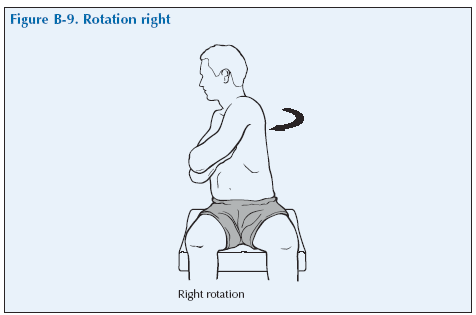

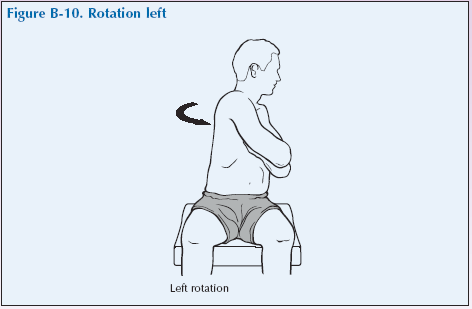

Sitting Rotation

Ask the patient to sit comfortably facing you on the edge of the examining table with legs hanging free. Ask them to turn their upper trunk as far as possible to the right. Gently guide their shoulders to ensure that the maximum range has been reached. Repeat this procedure to the left

What have you found?

Listen

Listen for any signs of crepitus.

Special tests

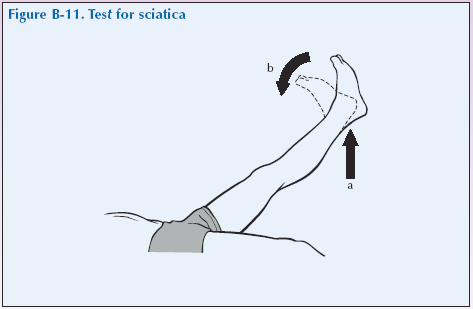

The lumbar spine is a region where nerves can easily be compressed. The examination of the lumbar spine should therefore include neurological examination of the lower limbs and the performance of tests that detect the presence of tension affecting the nerve roots in either the femoral or sciatic nerves, which are nerves supplying the legs.

Lightly touch the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the feet and toes and ask if sensation is normal. Test strength by asking the patient to dorsiflex the foot and the big toe against resistance and then plantar flex the foot against resistance. (Dorsiflexion or just flexion involves moving the top of the foot towards the shin and plantar flexion or extension, is the opposite movement otherwise known as pointing your toes).

Test for sciatica (sciatic nerve root compression) With the patient lying supine and the leg straight, gently raise the patient’s leg from the bed observing for distress and asking about pain in the back or down the leg. Normally you should be able to raise the leg to 60° – 90°. An angle of less than 60° because of pain is a positive result. Tight hamstring muscles, which may limit leg movement and cause pain behind the knee must be distinguished from true sciatica. Pain down the leg distal to the knee suggests sciatic nerve root compression. When the ankle is dorsiflexed any increase in pain confirms the presence of sciatic nerve root compression. Repeat the test with the other leg.

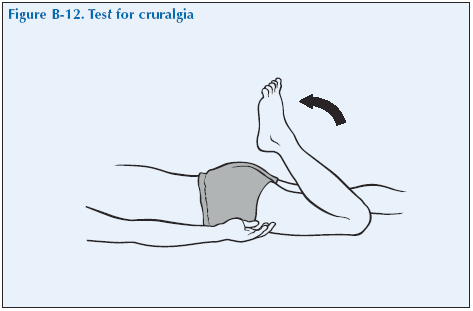

Test for cruralgia (femoral nerve root compression) Cruralgia is not as common as sciatica. This test involves stretching the femoral nerve and looking for pain in the anterior thigh of the same leg. With the patient lying prone and relaxed take hold of the patient’s ankle and passively flex the knee as far as it will go without causing discomfort or distress. Pain in the anterior thigh indicates compression of the roots of the femoral nerve on that side. Repeat the test with the other leg.

“We have now come to the end of this mock consultation. You should have learned quite a bit about my condition from taking my history and examining my joints, however, I would be happy to provide you with a bit more detail about the progress of my condition and how it affects my life, if you would find this useful.”

[Please give a brief description of your condition:

- When and how it started.

- Physical and psychological affects on you.

- Treatments offered.

- How your condition progressed.

- How this affected your life: Home, education, work, leisure, ability to travel, relationships etc.]

“Does anyone have any further questions?”

“Thank you again for attending this session. I hope you have found it useful.”

Lateral flexion

Ask the patient to bend to the right and then to the left as if trying to edge his/her fingers as far as the knee. Usually the finger tips should reach as far as the middle of the thigh. Reduction of lateral flexion is typically seen in ankylosing spondylitis but is characteristically relatively well preserved in mechanical low back pain and disc prolapse.