Introduction: The Wrist & Hand

The hand possesses remarkable ability to grip and feel. We use our hands to explore our environment, to communicate, to write, use a keyboard, drive a car, to manipulate and use tools and numerous other activities. Impairment of wrist and hand function can therefore have a major impact on lifestyle.

Anatomy of the wrist and hand

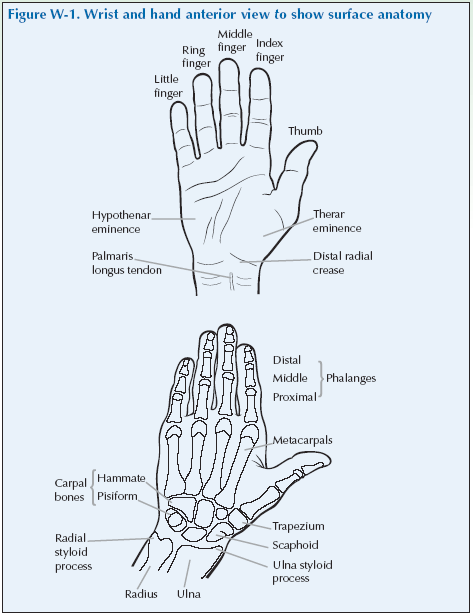

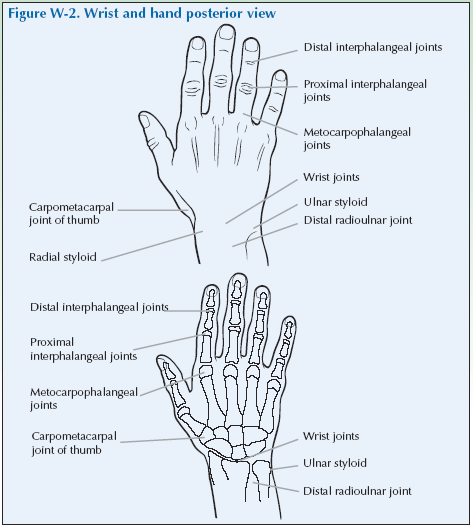

The forearm is connected to the hand by the wrist. The bones in the forearm are known as the radius and ulna, the ends of which flare out to form the radial styloid and the ulnar styloid. The bones of the wrist are known as the carpal bones and they are arranged in two rows of four bones. The carpal bones articulate with the metacarpals to form the body of the hand and the fingers are composed of three phalanges (singular is phalanx); the thumb has only two phalanges.

The thumb therefore has three joints: the carpometacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb, the metacarpophalangeal joint and the interphalangeal joint. The fingers have a metacarpophalangeal joint and two interphalangeal joints so these are called the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints and the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints.

The naming of these joints is quite logical:

Where the radius is attached to the ulna at the wrist

➞ distal radio-ulnar joint

Where the radius and ulna join the carpus

➞ wrist joint

Where the carpal joins the metacarpals

➞ carpometacarpal joint

Where the metacarpals join the phalanges

➞ metacarpophalangeal joint

Where one phalanx joins another phalanx

➞ interphalangeal (or between the phalanges) joint

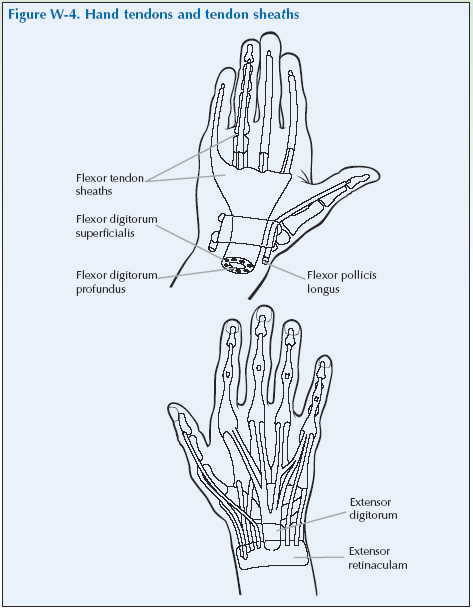

The muscles that flex and extend the wrist and fingers are in the forearm and tendons run from them to the wrist and fingers. There are small muscles in the hands responsible for some movements of the thumbs and fingers.

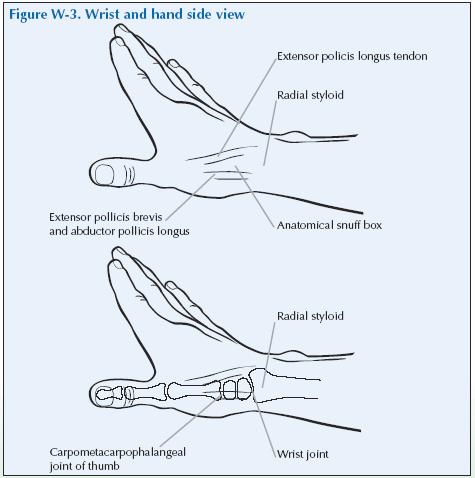

On the anterior aspect are the flexor tendons and on the posterior aspect are the extensor tendons. These tendons are enclosed in tendon sheaths which are lined with synovial cells (like those lining a synovial joint) that produce fluid. The sheaths minimise friction and facilitate movement. Tendons can become inflamed (tendinits).

De Quervain’s tenosynovitis is an inflammation of the tendon sheath in the thumb region.

The flexor tensdons are covered by the palmar facia. Thickened tendons are rope-like structures and are sometimes noticed when the palm is palpated, when they can be felt to roll as they are moved back and forth.

In between the metacarpals are the intrinsic muscles. The thenar eminence is a fleshy part of the hand located at the base of the thumb and the hypothenar eminence is the fleshy region located at the base of the little finger.

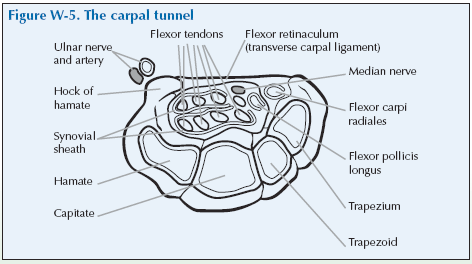

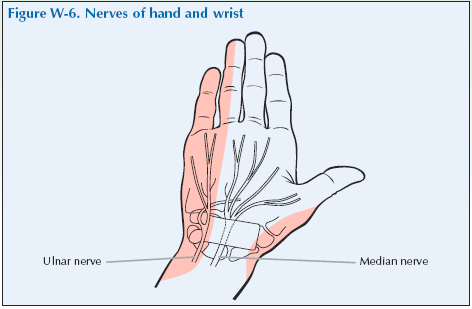

An important feature of the wrist to remember is that the hand is supplied by two nerves the median nerve and the ulnar nerve. The median nerve at the base of the wrist runs through the carpal tunnel, formed by the transverse carpal ligament and the carpals at the anterior aspect of the wrist, then into the thumb, second, and third finger and the lateral aspect of the fourth finger.

The ulnar nerve is one of the major nerves of the arm. It originates in the neck and runs down the inner side of the upper arm to behind the elbow. In the forearm it supplies the muscles with motor nerves (nerves that make the muscles move). Lower down it divides into branches that supply the skin of the palm, the lateral aspect of the fourth finger and the little or fifth finger. The ulnar nerve does not pass through the carpal tunnel. Therefore compression of the median nerve will produce sensations in the thumb to the medial side of the fourth finger, but not the lateral aspect of the fourth finger or the fifth finger, which is supplied by the ulnar nerve.

Problems of the wrist and hand

A wide range of problems can affect the hand and wrist. There may be osteoarthritis or inflammatory arthritis (most commonly RA) affecting the joints, inflammation of the tendon sheaths (tenosynovitis), carpal tunnel syndrome, injuries and infections. Pain in the wrist and hand can be referred from the neck but the sensation is usually more of a tingling than pain. Difficulty with hand movement can be due to thickening of the palm due to Dupuytren’s contracture and swellings can be due to ganglions or rheumatoid nodules.

[su_table]

Periarticular causes

| Tenosynovitis | Trigger finger, de Quervain’s tenosynovitis |

Articular causes

| Osteoarthritis | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | This can be acute or chronic |

| Other types of arthritis | Other types of arthritis |

[/su_table]

Other conditions

[su_table]

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | Peripheral entrapment of the median nerve may give rise to carpal tunnel syndrome |

| Reflex sympathetic dystrophy | Dupuytren’s contracture (algodystrophy, Sudek’s atrophy) |

| Ganglions | Peripheral entrapment of the median nerve may give rise to carpal tunnel syndrome |

| Infection | Soft tissue infections of the hand are common and need to be always considere |

[/su_table]

Rheumatoid and osteoarthritis both cause characteristic findings in the hands and fingers that are described below.

The hands and arthritis

The hands provide several clues to diagnosis of many forms of arthritis so it is worth being aware of some of these signs and symptoms. Listed are some of the changes you might find in people with different types of arthritis; some of them will only be apparent in people who have had the conditions for a long time. You may have some of these signs it will depend on your type of arthritis:

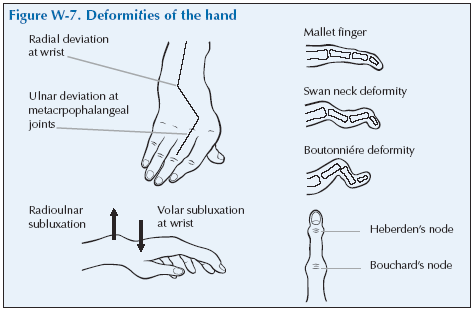

- Bony swelling of the joints: OA can cause bony swelling of the PIP joints (Bouchard’s nodes) and the DIP joints (Heberden’s nodes). (As an aide memoire: B comes before H in the alphabet and the proximal node comes before the distal node).

- Squaring of the hand is caused by OA of the thumb base enlarging the carpometacarpal joint.

- Subluxation: Partial or incomplete displacement of the bones of the joint.

Dislocation: The bones of the joint are completely displaced so that they are no longer in contact.

- Ulnar deviation: The metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint changes in response to the chronic synovitis of RA. The long axis of the fingers deviate in an ulnar direction from the MCPs as the supportive muscles, tendons and ligaments atrophy.

- Swan-neck deformity: Chronic swelling at the PIP joint due to RA causes displacement and pulling of the extensor tendon. The PIP joint becomes hyperextended and the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) develops a flexion contracture. (A contracture occurs when there is thickening or scarring of connective tissue caused by inflammation. It results in joint deformity. A flexion contracture will hold the joint in an abnormally flexed position).

- Boutonnière deformity: The swelling produced by RA weakens the supportive structures of the joints and the extensor tendon slides to the palmar aspect of the finger. The PIP joint develops a flexion contracture and the DIP joint is hyperextended.

- Skin and nail changes: Signs of complications of RA and of psoriasis can be seen in the skin of the finger tips and nails

- Intrinsic muscle wasting: Loss of strength and/or size of the muscles of the posterior aspect of the hand, which are involved in flexion, abduction and adduction of the fingers.

- Rheumatoid nodule: A cluster of fibrous (thickened or scarred tissue) forms under the skin and appears as a knot or swelling.

Giving a history of wrist and hand problems

The doctor should first ask you ‘What is the problem?’ and you should give a short response describing your symptoms and their effect on your quality of life.

Describe as fully as you can your own symptoms, including where in the hand you feel/felt pain or discomfort, what manipulations of your fingers or hand have become difficult or impossible, and whether you have/had any tingling in your arms and/or hands. Say if you have any stiffness, swelling or other symptoms. Mention how the problem is having/had an impact on your daily life, your work or your sleep.

Remember to describe how your condition affects/affected your quality of life using the framework covered in the earlier section of this manual. Consider self care (e.g. ability to wash, dress, toilet and feed), domestic care (e.g. ability to cook, clean, launder, shop), work (e.g. ability to stand, sit, type), leisure (e.g. ability to play sports, walk, go out for meals). Explain about the way it limits/limited your activities and restricts/restricted your participation in normal life.

Do not tell him everything spontaneously – just the important part. He will then need to ask further questions to fully characterise your problem. Develop a set of answers with your trainer to the following points. Prompt them if they omit important questions.

Pain is usually present and questions should establish:

- How the pain started and developed.

- The nature of the pain.

- The exact distribution of the pain.

- Whether the pain has increased or decreased over time.

- Whether it affects sleep.

- Whether anything exacerbates or relieves the pain. Stiffness may be a symptom and questions should establish:

- If you are stiff at all?

- When it is worse?

- What improves it?

Swelling may be a symptom and questions should establish:

- If you have noticed any swelling and where.

- If it is always present.

- If it is painful or tender.

- If it is increasing.

They need to ask about patterns of symptoms – which joints in the hand are affected and whether any other joints in the body are involved.

You may prompt the doctor (if you have not already told them) to make sure that they include the following information:

- Your hand dominance.

- Your age, occupation and hobbies.

- Your past medical history.

- Whether you have injured your hand or recently done a lot of repetitive activities with your hand.

- Whether there is any impairment of function and how this impacts on your daily activities.

– Hand and wrist problems typically produce difficulties in brushing or combing hair, dressing, holding a toothbrush, driving car, preparing food, using utensils, cooking (lifting cookware) writing or typing, turning keys in locks and opening doors.

- Whether you have any symptoms such as tingling in your hands/fingers or stiffness.

- Whether you have had previous treatment and if so whether it was successful.

If you personally do not currently have hand or wrist problems then tell the trainee this fact and just remind the trainee of the points they should cover when taking a history.

The effect of any problem depends on your personal circumstances. The doctor needs to know about what you need to do in the home, at work, your leisure interests and your expectations.

You may have symptoms affecting other parts of your musculoskeletal system. You may prompt the doctor to ensure he has asked whether you have any other problems affecting your muscles, other joints, neck or back.

You may go into further details about how your problem affects your life and the treatment you have received at the end of the session when discussing the findings.

Example of a Script

You should develop something like this, based on your own story. First you need to ask me:

“What is your problem?”

“I have had a pain in the hand and difficulty making a grip for the last five years, it has gradually worsened and I cannot now do things which need a good grip.”

You should then respond to questions, guiding and prompting the doctor through the information as listed above.

Wrist and Hand Examination Script

“I would now like to invite you to find out a little bit more about

my problems, by role play, using me as your patient and examining me.”

Look

Inspect the anterior and posterior surfaces of the hands and wrist for redness, swelling, muscle wasting, skin changes and changes in alignment. Inspect the nail and nail beds.

Observe the position of the hands and wrists in motion to see if movements are smooth and natural.

Look at the palm for redness and wasting of the thenar and hypothenar eminences.

Look for swelling over the dorsum (the back of the hand). Over the wrist and distal hand it may be of the joint or extensor tendon sheath. When the fingers are actively extended, swelling of the extensor tendon moves (Called the tuck sign).

Look for swelling of the MCP joints which will fill in the valleys between them. This is easiest to see if you ask the patient to make a fist and you look at the profile from the front to see if there are the normal peaks and troughs.

Look for squaring of the palm base because of swelling of the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint as seen in OA. Look at the proximal (PIP) and distal (DIP) interphalangeal joints. There may be bony swelling of the PIP and DIP joints with some malalignment of the distal phalanges in OA.

In established RA there may be changes at the wrist such as volar subluxation (volar means relating to the palm of the hand or sole of the foot) and radial dislocation at the wrist with dorsal subluxation of the ulnar styloid. Typical deformities in the hand are ulnar deviation of the fingers at the metacarpal-phalangeal joints, hyperextension at the proximal interphalangeal with flexion at the distal interphalangeal joint (swan neck deformity) or flexion at the PIP with hyperextension at the DIP (Boutonnière deformity). A Z-shaped finding in the thumb can be seen in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Wasting of the thenar eminence may be indicative of nerve involvement (such as with carpal tunnel syndrome) or may just be reflective of the disease, the ageing process or loss of function.

What do you see?

Feel

Assess the wrist and hand generally for heat using the back of your hand.

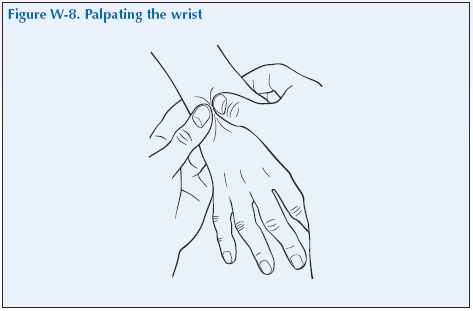

Palpate the wrist

Palpate the wrist by placing your two thumbs on the posterior aspect of the wrist and use your remaining fingers to support the wrist. Ensure the arm is generally supported, such as by resting the elbow on the arm of the chair.

Palpate the distal radius on the lateral surface and the distal ulna on the medial surface. Palpate the groove of the wrist joint with your thumbs. Palpate the carpal bones with your thumbs.

Feel gently for any swelling using the flat of the thumb tips. Increase pressure to establish if any swelling is tender. As a rule it is not necessary to press harder than the pressure that will make the thumbnail bed blanch or whiten.

To measure joint tenderness, find the joint line by flexing and extending the wrist and then gradually increase the pressure with your thumbs either until the patient says it is uncomfortable or until your thumbnails blanch or whiten.

Ask the patient to flex and extend, helping them as you palpate their wrist joint to feel for crepitation.

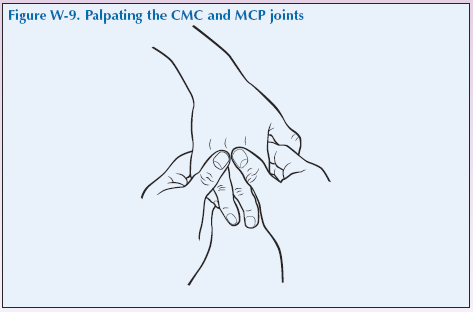

Palpating the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint

Palpate the CMC joint of the thumb first, since it’s easy to forget it. Support the patient’s hand with the cupped fingers of your two hands and use your thumbs to palpate on both sides of the joint. Check the joint for swelling and tenderness by gradually increasing pressure until tenderness is established or up to a maximum of when your thumbnails blanch or whiten. Feel for crepitation as you and patient move the thumb. This is a feature of OA and this joint is very common site for this finding.

Palpating the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints

Support the patient’s hand with the cupped fingers of your two hands and use your thumbs to palpate on both sides of the joint anteriorly with your fingers feeling the palmar aspect of the joints. Then work your way across the MCP joints, one by one. Palpate each joint with both thumbs over the joint line, which is just distal to and on each side of the knuckle, and with the index fingers feeling the head of the metacarpal in the palm. Gradually increase pressure until tenderness is established or up to a maximum of when your thumbnails blanch or whiten. Note any

swelling, bogginess, tenderness, subluxation and dislocation.

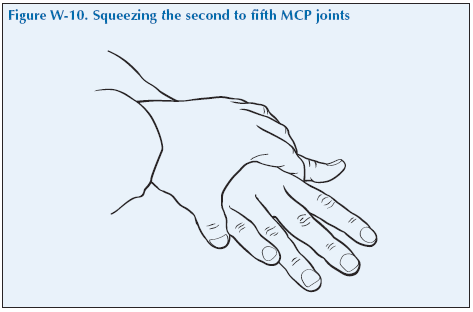

Squeezing across the second to the fifth MCP joints together can be used as a composite assessment for tenderness of the MCP joints but needs to be done gently as can be very painful if the patient has synovitis of several joints.

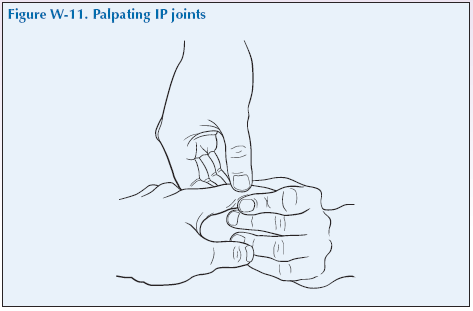

Palpating the interphalangeal (IP) joints

Ensure the patient is comfortable holding their arm up or rest the elbow on a surface such as the arm of the chair.

There are two common ways of palpating the IP joints and we are going to teach one of these. Just explain to the doctor that they may have seen it done differently but that this is the way you were taught.

Palpate the interphalangeal (IP) joint of the thumb by using your thumb and first two fingers to surround and squeeze the joint and feel for any swelling, bogginess and/or tenderness. Remember about how hard to squeeze – the same rule applies.

Palpate each PIP joint with the finger and thumb of one hand squeezing from the sides and the other finger and thumb squeezing from front and back. You can judge if there is swelling of the joint and if it is bony or soft tissue due to inflammation by a gentle squeeze from the sides, feeling with the other thumb and finger for any movement of soft tissue front and back, and then a gentle squeeze from the back and front whilst noting any movement of the swelling at the sides.

Soft tissue swelling could indicate RA, and bony enlargement

(Bouchard’s nodes and Heberden’s nodes) may indicate OA.

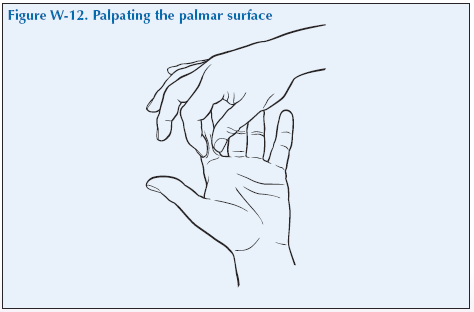

Palpating the palmar surface

Palpate the palmar surface of the hand along the tendons whilst moving the fingers to distinguish between joint and tendon pain. Check for tendon thickening in the pulp of the fingers between the MCP and PIP joints. When palpating the palmar facia, joint pain is likely to be at the MCP head. Pain proximal to the MCP is likely to be tendon pain.

Trigger finger – A painless nodule develops on a flexor tendon in the palm, near the head of the metacarpal. The nodule is too big to enter easily into the tendon sheath when the person tries to extend the fingers from a flexed position. With extra effort or assistance, the finger extends with a palpable and audible snap as the nodule pops through the narrow area. This snap may also be evident during flexion.

What do you feel?

Move

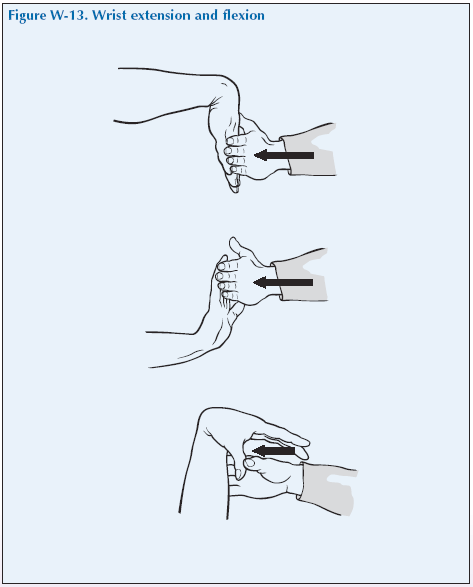

The motions of the wrist are flexion, extension, radial movement, ulnar movement, supination and pronation.

Flexion and extension of wrist

Ask the patient, with their arms in front and elbows at 90° and palms facing down (pronated), to flex their wrist and then extend it. If it is limited, then hold the patient’s forearm proximal to the wrist with one of your hands and with the other gently coax the patient’s hand downwards and then upwards until the maximal range of movement is reached without causing pain. The normal maximum movement is to 60–90° of flexion and of extension.

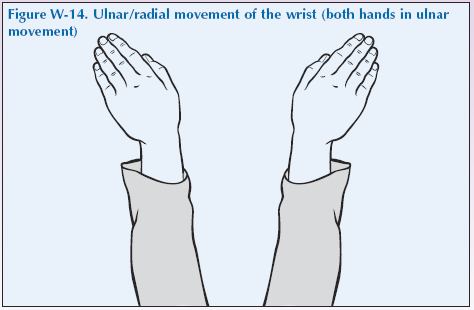

Ulnar/radial movement

Ask the patient to then move their hands from side to side.

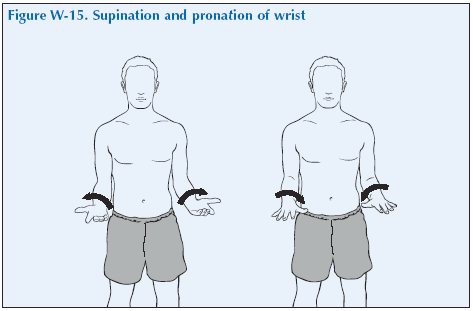

Supination and pronation of wrist

Ask the patient to rotate their forearms so that their palms face upwards (supination) and then back so that their palms are again facing down (pronation).

Flexion of the fingers

Ask the patient rotate their forearm again so that the palm faces upwards. Then ask them to make a fist to evaluate the MCP, PIP and DIP joint movement. They should be able to make a tight fist with the fingers reaching the palm if the range of flexion of the MCP, PIP and DIP joints is normal. Inability to do this shows there is a problem either affecting the MCP, PIP or DIP joints or a problem affecting the tendons (tenosynovitis or rupture) or soft tissues of the hand.

If limited, gently use pressure until maximum range is achieved without causing pain to see if the passive range is greater. If the patient is unable to flex a finger actively, but is able to flex it passively, it could indicate a flexor tendon rupture.

As they open their hand note how blanched the palmar surface is – this gives some indication of how strong their grip is.

Extension

Then ask the patient to extend their fingers. If they are unable to extend a finger fully actively, use gentle pressure until maximum range is achieved without causing pain to see if the passive range is greater.

If they are unable to extend a finger actively or passively, it is called a fixed flexion deformity. If the patient is unable to extend a finger actively, but is able to extend it passively, it could indicate an extensor tendon rupture.

Tendon rupture may happen due to bony changes and inflammation in the hand, flexor tendons often in the palm and extensor tendons at the wrist. Many tendons pass through the wrist, hand and fingers. The tendon sheaths may become swollen and tender and with chronic inflammation, the ulnar styloid may become jagged, which could cause damage to the tendon as it slides over the rough bone, eventually causing it to rupture.

Passively extend the fifth digit to look for hypermobility.

If you are in doubt about whether the Range of Motion (ROM) is full or limited, compare it with your own ROM.

Grip strength

Ask the patient to grasp second to third fingers of each of your hands at the same time. You are evaluating overall grip strength, as well as whether one hand is significantly stronger or weaker than the other.

Pinch grip

Then ask the patient to make a pinch between their thumb and each of their fingers. You can test the strength by trying to break the circle they make between finger and thumb.

Note: if you are a Patient Partner with reduced or unequal grip strength you could ask “What do you notice about my grip strength?”

What have you found?

Stress

There are no stress tests that need to be done routinely.

Listen

Listen for crepitus as the patient moves their wrist. You cannot usually hear crepitus from the finger joints.

Special tests

Special tests may be performed if appropriate for that particular patient:

- Piano Key sign: The ulnar styloid lowers and bounces back as you press on it, suggesting that the ligaments and tendons may have been weakened by synovitis of the distal radio-ulnar joint.

- Tinel’s sign: Tingling or numbness along the distribution of the median nerve (the thumb first, second and side of the third finger) is elicited by tapping over the median nerve as it runs through the carpal tunnel (tap the ‘bracelet lines’ of the wrist). A positive sign may be indicative of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, which is caused by compression of the median nerve as it passes through the carpal tunnel.

- Finkelstein’s sign: Passive ulnar flexion with the thumb held tucked underneath the flexed fingers stretches adductor and extensor tendons and reproduces the pain of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis.

“We have now come to the end of this mock consultation. You should have learned quite a bit about my condition from taking my history and examining my joints, however, I would be happy to provide you with a bit more detail about the progress of my condition and how it affects my life, if you would find this useful.”

[Please give a brief description of your condition:

- When and how it started.

- Physical and psychological affects on you.

- Treatments offered.

- How your condition progressed.

- How this affected your life: Home, education, work, leisure, ability to travel, relationships etc.]

“Does anyone have any further questions?”

“Thank you again for attending this session. I hope you have found it useful.”